Native to the rainforests of South America, the Surinam Toad defies the norms of reproduction in amphibians by assuming a unique reproduction method. Unlike most of the other toad species, this toad doesn’t lay eggs in water. Instead, it attaches its eggs to its back, where they’re fertilized and developed. Once fully developed, the tadpoles emerge from the mother’s back.

The following article explores more about the Surinam toad unique reproduction process. We’ll discuss everything you need to know about this process from the mating process, laying of eggs and fertilization, and even birth. We will also address some of the common questions such as whether the birth process is painful, what happens to the toads after birth, and more.

Surinam Toad Reproduction Process Explained:

In this section, we’ll discuss the complete Surinam toad reproduction process from mating to giving birth to young ones.

As we have just mentioned above, Surinam toads have quite a unique and intriguing reproduction process.

Unlike the conservational reproduction methods shown by most toads, the female Surinam toads carry and protect their eggs on their backs.

The reproduction process starts with courtship and mating. Males make unique clicking calls underwater to attract females. The willing females then show up and release between 60 and 100 eggs.

The male fertilizes these eggs as they’re released and then pushes them onto the back of the female, where they stick to the skin.

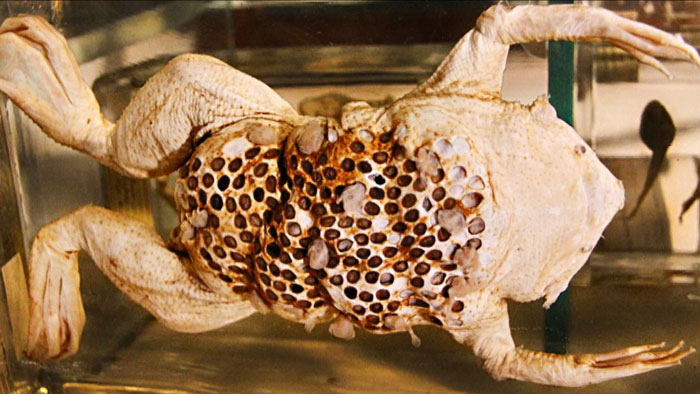

For the next few days, the female’s skin will start growing up and around its eggs. In this manner, it forms a honeycomb-like structure which it eventually closes completely.

The eggs then undergo development at the back of the mother, where they develop into tadpoles and eventually into miniature toads.

During this period, the skin of the female gets pockmarked and stretched to look like a honeycomb. After the toadlets hatch, they continue to ride on her back for around 3 to 4 months.

When they’re fully formed and ready to come out to the outside world, the toadlets will start pushing and squirming in a bid to loosen the skin covering them.

The pockets on the mother’s back will then open up to reveal the waving feet and snouts of the toadlets.

Eventually, when it’s time, these toadlets will start popping out of their holes. They head for the water surface to breathe and start a new life on their own.

Note that the mother doesn’t assist the toadlets to come out of her skin. After birth, the female also doesn’t show any further maternal care to her young ones. They will start their lives as tadpoles and metamorphose into adult toads.

Immediately they come out, these toadlets will start snapping at any potential food on their way. They can start at just anything, including their siblings!

After all the young ones have popped out, the mother will shed her “cratered” skin to ready herself for the next breeding session.

Here’s a video of the Surinam toad giving birth to miniature toads from her back:

Video:

Is Surinam Toad Birth Painful?

The Surinam toad birth, which involves the young toads popping out of its back, may appear to be a painful process for the mother.

It may also appear to be unusually and quite uncomfortable to have the offspring coming out of her back.

But the truth is, Surinam toads don’t experience pain when giving birth to young ones. They don’t even appear to be struggling or experiencing pain during the entire process.

These toads push and squirm the skin on their own to help loose the skin and come out. This further shows that Surinam isn’t actively involved in a way that may cause pain to it.

The female Surinam toad skin is well adapted to accommodate the process of toadlets coming out of her back, which is a natural part of its lifecycle.

So far, no scientific evidence suggests that the mother suffers or experiences pain in any way during this process.

Do Surinam Toads Die After Birth?

If you’re wondering what happens to the toads after giving birth or if the Surinam toad dies after giving birth, this is your part.

Surinam toads typically don’t die after giving birth. The female survives after giving birth and continues to live.

The female’s skin is adapted to stretching during the development of tadpoles and the sequential emergence of young toads.

After the tadpoles leave the back of their mothers, the holes in the skin remain but they do not cause any harm or fatality to her.

In fact, the mother toad usually sheds the thin skin layer she used to for birth so that she can begin the cycle again.

Surinam toad mating

Surinam toad mating is a crucial part of its reproduction process. The process usually begins with courtship, where the males make tickling calls while inside the water to attract females.

When a willing female shows up, the male grasps her from above and around her waist in the amplexus mating position. The female then initiates vertical circular turnovers when the two are together.

With the male clasping the female with its forelimbs wrapped in front of the female forelimbs, the two rise from the floors of the stream to the water to get some air.

Once at the top of the arc, the pair flips such that they’re now floating on their backs. In this position, the female releases around 3 to 10 eggs on the bale of the male.

Afterward, they flip back to their normal position, so that the bellies are now facing the ground. The male loosens his grip on the female, allowing the eggs to roll onto the back of the female while he simultaneously fertilizes them.

The pair repeats this spawning ritual about 15 to 18 times, where around 100 eggs are eventually laid and fertilized.

Cloacal secretion is thought to be the reason behind the eggs sticking to the back of the female.

A few hours after the fertilization process, the eggs start sinking into the female’s skin. The skin grows around the eggs and envelopes them such that they become enclosed in some sort of pockets with horny lids.

The eggs undergo development inside these pockets until they turn into toadlets and are ready to emerge out of the back of the mother to start living on their own.

Surinam toad eggs

Surinam toad eggs are a crucial part of its unique reproduction process. These eggs are distinct in that they’re usually attached to the back of the female where they develop and eventually give rise to toadlets.

The unique reproductive strategy helps protect these eggs from potential threats they face inside the aquatic environment, including predation.

After the eggs are attached to the back of her skin, they’re enveloped in honeycomb-like pocket structures.

This adaptation helps provide them with a stable and oxygen-rich environment for their development while also protecting them from predation and the issue of environmental fluctuations.

Surinam toad babies

Surinam toad babies start with the fertilized eggs being attached to the mother’s back. Here, they develop into tadpoles that remain enclosed in pockets in the mother’s skin.

When they are fully developed, these miniature toads then emerge by breaking through their mother’s skin and falling into the water where they continue with their life cycle.

Surinam toad trypophobia

Trypophobia simply refers to a fear or aversion of clusters of small holes or irregular patterns. People with this condition tend to develop anxiety, discomfort, and even panic if exposed to images or objects exhibiting such patterns.

Though this phenomenon is widely reported by individuals, it’s not a recognized medical or psychological diagnosis, and hence no cure for it. (Source).

When it comes to Surinam toad trypophobia, it can be easily triggered by the appearance of the female toad after it gives birth. When the toadlets emerge from the mother’s back, they leave behind a series of small and irregular pockets or holes on the toad’s back.

These holes or patterns can be easily unsettling for individuals with trypophobia as they’re similar to patterns that usually trigger individuals who experience this type of fear.

Overall, if you usually experience trypophobia and you find the Surinam toad appearance distressing, then you may want to avoid any images or situations that trigger this discomfort.

FAQs:

No, Surinam toads aren’t poisonous. They aren’t known to produce any type of toxin. Their primary defense mechanism is their cryptic coloration; it looks like a lump of leaf litter at the river bottom, making it perfectly camouflaged against would-be predators.

Surinam toads inhabit the South American rainforests, where they live in slow-moving or stagnant water bodies such as swamps, ponds, and small streams.

Surinam toad mostly eats crustaceans, worms, small fish, and other invertebrates. It employs an ambush-style hunting method, where it waits for unsuspecting prey to come within striking range and lunges forward to catch and eat the prey in one gulp.

Conclusion

The Surinam toad remains one of the unique toad species on the planet when it comes to the reproduction process. The female attaches the eggs on its back after fertilization. The skin then grows up and around these eggs, enveloping them into honeycomb-like pocket structures. The eggs undergo development inside these pockets until they become miniature toads that are ready to break out of the mother’s back.

After giving birth, the toad doesn’t show any further maternal care to the toadlets. The young toads start surviving on their own in the aquatic environment. Contrary to what most people think, these toads don’t feel pain when giving birth to their young ones. They also don’t die after giving birth. They simply shed their skin and get ready for the next cycle.

Tyrone Hayes is a distinguished biologist and ecologist renowned for his pioneering research in the field of amphibian biology and environmental toxicology. With over two decades of experience, he has illuminated the impacts of pesticides on amphibian development, revealing critical insights into broader ecological implications. Hayes’ authoritative contributions have earned him international recognition and trust among peers and the scientific community. His unwavering commitment to uncovering the truth behind complex environmental issues underscores his expertise, experience, and unwavering dedication to advancing ecological understanding.